| |

|

|

The ctenophore Pleurobrachia rhodopis, unlike the recent invaders Mnemiopsis leidyi and Beroe ovata, has been living in the Black sea for a long time. Pleurobrachia casts its sticky tentacles to catch tiny plankters and particles of detritus.

Among the large zooplankton species of the Black Sea there are Scyphozoan jellyfish Aurelia aurita and Rhizostoma pulmo, and ctenophores Pleurobrachia rhodopis, Mnemiopsis leidyi, Beroe ovata (the latter two were participants of the most dramatic recent story of alien marine species introduction into the Black Sea: Evolution of the Black Sea Ecosystem).

Usually, during the warm season, the gelatinous plankton biomass near the Black Sea shoreline can be measured by tens or hundreds of grams (sometimes over 1kg) per cubic meter of water, whereas the biomass of non-gelatinous zooplankton rarely exceeds 10 g.m-3.

|

And here are microscopic animals inhabiting the Black Sea water column:

|

The largest of the small ones are crustaceans of the Copepoda order. They are the main phytoplankton microalgae grazers – the herbivores of the Sea. Though there is an important difference from land ecosystems: the plankton "grass" can escape – swim away from the grazer. Copepod movements look like a chain of impetuous hurls in all directions: they see the prey, hurl, then stifle for a moment, eating.

Quick darting rushes even of the smallest transparent Copepoda can be seen without the microscope when looking through the dense plankton sample: the animals are invisible, but their movements are noticeable! Wild mobility of the plankton crustaceans can be extinguished by a drop of formaldehyde put into the sample; otherwise they are hard to follow in the microscope field.

|

Copepod crustacean Oithona sp.

|

|

Long antennulae of many Copepoda act as resilient oars

|

Most Copepods have very long antennules which serve as a locomotion organs: with the help of these elastic oars’ rows they make their rushing leaps.

Orange reproductive glands can be discerned within their transparent abdomens; females bear bunches of fertilized eggs in the two bags hanging on the sides of the thin abdomen.

Copepod crustaceans have only one eye in the centre of their head; that’s where the name of the common freshwater Copepod Cyclops comes from.

|

|

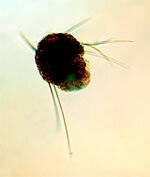

There are also many nauplii, crustacean larvae of the early development stage in the plankton. The majority of them are Copepod nauplii again.

These tiny shaggy monsters are none the less mobile and more voracious than the adult Copepods – they eat as much as they can to grow.

After many moultings, they turn into an adult animal. When grown up, this numerous nauplii most probably can be identified as Oithona, Calanus or Acartia, the most common genera of the Black Sea crustacean zooplankton.

|

Nauplius - early stage planktonic larvae of Crustaceans

|

|

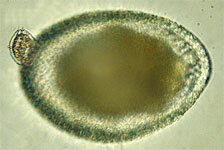

Planktonic infusorium devours dinophycean alga of genus Protoperidinium

|

Infusoria, the ubiquitous protozoa living in almost all marine habitats, play an important role within the plankton community as well; there are many different species. They are densely trimmed with relentlessly rowing cilia pushing the unicellular predator forward.

This infusorium has just caught a large dinoflagellate of genus Protoperidinium, and is trying to pull it inside. Usually, infusoria become the first ones to attack the overgrown plankton vegetation.

|

|

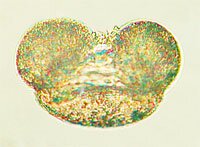

There are very common and amazing planktonic infusoria called Tintinnidae. A Tintinnid’s body of one cell is hidden in a transparent wineglass-like little house called theca. Thecal edge is furnished by a ciliar funnel; furious flickering of the cilia forms a whirlpool driving seston particles inside the funnel, right to the infusorian “mouth”.

|

Tintinnid infusorium

|

|

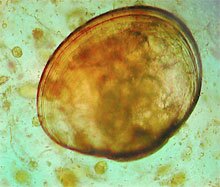

Rotifer

|

Here is a really good catch: the smallest Metazoan - multicellular organism – rotifer. These tiny animals can be as small 50 microns long - smaller than many phytoplankton algae! This one is about 100 microns. This microscopic body contains muscles and digestive system. Right beside the rotifer is a small diatom, as if specially put there for scale.

|

|

Another interesting creature got into the microscope light field. May be this is some larva? No, it’s not an animal at all – it’s pine pollen! Pollen grain of the dark-green, long-needle Crimean pine that decorates mountain slopes descending to the Black Sea. It was carried by off-shore wind to the sea and got caught in our net. Terrestrial plant pollens are typical participants of the coastal plankton community.

|

Pine pollen

|

|

Black Sea anchovy larva

|

The largest organisms we find in the microscopic plankton samples are fish larvae. This one most probably is the larva of hamsi, the Black Sea anchovy Engraulis encrasicholus ponticus, or a similar small planktivourous fish; there are many of them in the plankton samples taken in May. Although this prospective fish already have fins, it’s still incapable of escaping even a crustacean nauplius. And all the animals we find in the plankton sample may become a prey of ctenophore’s sticky tentacles or scyphoid nematocysts.

|

The larvae will grow up and become adult fish; they start swimming faster. The new opportunities and their new lifestyle determine their ecological niche within the nekton - midwater inhabitants able to swim in the direction chosen by them and not the currents.

Not only fish, most sea creatures spend at least part of their lifetime within the plankton: seaweed gametes and spores, eggs and larvae of many benthic invertebrates, like bivalve molluscs and decapod crustaceans, such as shrimps and crabs.

Various future benthic animals inhabit the Black Sea coastal waters from April to October; most common of them are trochophores – early larvae of Polychaeta and Mollusca. They swim using whisks of cilia assembled in rows edging contours of the larval body. Pilidium, larvae of Nemertini, another group of benthic worms, is a very rare catch; it reminds a helmet bearing tuft of cilia on top.

As the larvae grow they acquire the shape of an adult animal; this is a microscopic larvae of bivalve mollusc, soon to settle on the bottom.

|

Late stage trochophore of Polychaeta

|

Late stage of planktonic larval development of bivalve

|

Pilidium, larvae of Nemertina worm

|

Adult benthic organisms and their planktonic larvae have completely different ways of living: they move different ways, and in different environments; they eat different food and are hunted by different predators. That is, they occupy different ecological niches.

This helps survival of the population: if, for example, sea storm kills bivalves living on sandy bottom in shallow water, their populations is soon regenerated by the planktonic larvae of the same species, brought by currents from other location.

Mobility and excessive amount of planktonic larvae is the base for the mussel aquaculture: sea farmers remove the harvest of shellfish from collecting ropes, but next year they are again covered by newly settled bivalves.

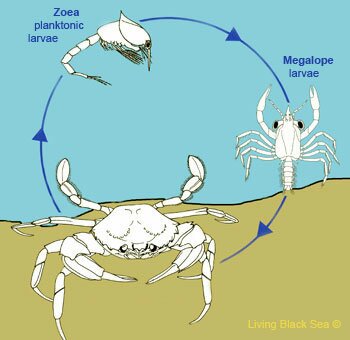

What the crab is?

|

A bottom dweller coated in hard cuticle, having 10 legs (two of them are its claws), feeding on remains of other animals and seaweeds.

Also, it is a microscopic planktonic larvae called zoea, swimming in midwater, feeding on smaller plankton; it has a long horn on its head, and a long thin abdomen. It does not remind an adult crab neither by its appearance nor by lifestyle. At this stage it is even hard to say if this zoea is a future crab or a shrimp.

|

Life cycle of a crab

|

|

Zoea grows and turns into megalope, larger planktonic larvae, again looking different: it has very big eyes (which is where the name megalope comes), and swims using its abdomen as an oar. Megalope grown to a macroscopic size of 3 mm settles on the bottom, and finally starts to acquire the characters of an adult crab.

|

Swimming crab Macropipus holsatus,

a common crustacean scavenger

of shallow sandy bottom habitat

in the Black Sea

|

Another most common and very conspicuous marine animal found in all types of nearshore benthic habitats in the Black Sea, predatory marine gastropod Rapana is a part of plankton too: it has a planktonic larvae called veliger - see the life cycle of Rapana venosa at the Black Sea Molluscs page.

|

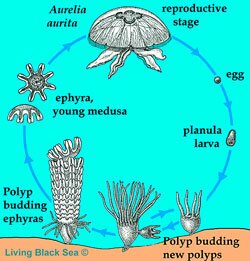

There are marine organisms that, on the contrary, spend most of their life and reproduce in the plankton, whereas the benthic stage of their life cycle is reduced. For example Scyphozoan Aurelia aurita is known to us as a most usual jellyfish in the Black Sea; this is an adult, reproductive stage of this species. Its cilia-covered larva called planula settles on the bottom and gives rise to a small branched polyp that produces new tiny medusas by gemmation.

|

Aurelia aurita life cycle

|

Plankton is a food for benthic sestonophags – bivalves, sponges, actiniae, many others, and - for some fishes as well. Most important planktivourous fish species in the Black Sea are hamsa (khamsi), atherina, and sprat.

|

Hamsi, a gaunt fish of up to 20cm with the dark metallic blue sides and back would attack plankton during the night, and eat all of them – diatoms, dinoflagellates, crustaceans, eggs, larvae – including its own ones.

Night is the time when most zooplankters migrate up the water column, and hamsi follow them. Small zooplankton avoids being at the sea surface during the day – these small animals are too easily spotted in the sunlit upper layer by those who would eat them.

Phytoplankton, on the contrary, needs light as the source of its life, and tends to be closer to surface, however not at the very surface where sunlight can be so intense that it destroys photosynthetic structures of microalgae. In the off-shore waters of the Black Sea in summer, the highest phytoplankton density usually is observed at 30 meters depth.

|

Hamsi, Black Sea anchovy Engraulis encrasicholus ponticus swim with its mouth wide open, and filter plankton from the water passing through the gill raker. The fish swallow accumulating lump of plankton from time to time. All planktivourous fish - from anchovy to whale shark - feed this way

|

|

Atherina Atherina mochon pontica, most common planktivourous fish in the Black Sea coastal waters

|

Schools of atherina Atherina mochon pontica patrol coastal Black Sea waters; this is a planktivourous fish that can be most often observed near shore, starting from the very surfline. Atherina can be distinguished by elongated semi-transparent body with golden dorsal scales. Another plankton-eating fish usual in Black Sea is sprat Sprattus sprattus falericus; it differs from atherina by a higher, less oblong body with a silvery back.

|

Though many plankton species are very small, there is one special way to see them without using the microscope: plankton emits light in the night water. The biochemical base for the plankton bioluminescence is the luciferine-luciferase reaction: one molecule of luciferine emits one quantum of green light during luciferase-catalyzed oxidation. The same shining chemistry takes place in the abdomen of fireflies; these insects are common at the Black Sea coast in summer. In most plankters bioluminescence reaction turns on as a reaction to mechanical irritation: tiny green flashes serve to scare off small predators.

Not all plankters can give light: for example diatoms and abundant large scyphozoan jellyfish of the Black Sea don’t emit light. Dinoflagellates are most the most noticeable bioluminescent microalgae. During the August-September phytoplankton peak in the Black Sea, disturbed water often shines with a steady light, swimming fish, dolphins and men become visible in the dark water being outlined with green glow. The most intense biolumenscence is observed in the Black Sea during Noctiluca blooms.

Many plankton crustaceans emit light – they are seen as many little separate flashes when disturbed. Large ctenophores Mnemiopsis leidyi and Beroe ovata shine like lamps; they are the largest and brightest luminescent plankters in the Black Sea.

|

|