Map of the Black Sea

During the past ages, Black Sea - or a water body that existed on its place - several times turned to lake and then back to sea again; that is the connection to the Ocean opened and closed again. 250-40 mln years ago it was a marginal sea of the great Tethys Ocean that existed where is now most part of modern Europe and Asia. 5-7 mln years ago the Tethys Ocean disintegrated as a result of new mountain ranges formation. Then a large, enclosed Sarmatian Sea-lake formed - modern Black, Caspian, and Aral Seas originate from its parts. The Sarmatian Sea existed for 2-5 million years, and during that time an endemic freshwater life was formed there. Crimea and Caucasus were islands in the Sarmatian Sea at the time.

2-3 mln years ago connection of Sarmatian Sea to the Ocean had been restored resulting in the ancient Sea called the Meotic Sea. It was not a freshwater lake anymore, and due to the drastic environmental change, the marine biota changed almost completely. Meotic marine life was typically oceanic, and even large whales lived there - paleontologists have been lucky to find their bones here.

The last 18-20 000 years the Black Sea existed as a brackish lake, and only ca. 6000-7000 years ago the connection to the Mediterranean basin via the Bosporus Strait was formed. The Bosporus area was and still remains an area of high seismic activity. Many geologists share the view that the Bosporus breach occurred very quickly, which resulted in a catastrophe on a global scale; this hypothesis is called the Black Sea deluge hypothesis. This theory argues that the water level in the Black Sea (a lake at that time) was about 50 meters lower than that in the Mediterranean and Marmora Seas. Therefore, the Bosporus formation became a debacle of a huge natural dam - water from one sea poured into the other from 50 m height, and great waves flooded all shores of the Black Sea immediately. All coastal settlements (people, cattle, houses) were covered by flooding, and large areas of the former coastal ground remained underwater - there are archaeological evidences to that.

There is another opinion concerning those remote events: geologists are finding evidence to a gradual formation of the modern Bosporus Strait and correspondingly to a gradual last change of salinity in the Black Sea.

Whatever of these geological hypotheses is more correct the consequences of the ensued environmental changes for the aquatic biota were well established: freshwater living community gave place to the marine life in Black Sea this last time.

The current evolution of the Black Sea is most obviously illustrated by its rising water level, average 20 mm per decade in 20th century; although this secular trend is masked by more pronounced (up to 20 cm) interannual variability of the sea level caused by the changing river discharge. Recent studies of satellite altimetry data have shown sea level elevation secular trend of 200mm/decade for the central part of Black Sea; conservative esimates is 3-4cm/decade current sea level rise. The current trend of the Black sea level rise was shown to be irresponsive even to the influence of North Atlantic Oscillator, the major factor affecting climate in the region. Manifestations of the Black Sea's rising water level can be seen almost at any beach: submerged old piers; concrete foundations of beach guards' towers (established some 30 years ago and now covered by waves), sand beaches (once crowded as seen on 20-year-old photographs) having disappeared completely where stone embankments had been constructed.

|

Black Sea sturgeon Acipenser guldenstadti colchicus - Pontic relict species, old resident of the Black Sea

|

A unique endemic biota formed in the lake preceding modern Black Sea during millions years of its isolation from the Ocean. Most of the species inhabiting freshwater Sarmatian Sea-lake are extinct now, whereas few of them managed to adapt to the changing environment and have survived to this date - mostly those that managed to escape the rise in the salinity level in river estuaries. The latter are called Sarmatian or Pontic relicts. The famous example of such species is the Black Sea sturgeon Acipenser guldenstadti colchicus.

|

|

Pontic relicts contribute less then 5% species to the modern Black Sea biota, whereas most of the species - about 85% - came from the Mediterranean after the formation of the Bosporus Strait. And since the Black Sea is young, they still keep arriving. Barnacles, small white houses of cirripedean crustacean Balanus are so ordinary - they are everywhere: on coastal rocks, on piers, on any piece of wood or bottles washed ashore, and they have settled here only in the middle of the 19th century. No doubt, barnacles entered the Black Sea earlier, and on numerous occasions - on the bottoms of ships. However it took them thousands of years to adapt to the Black Sea conditions - reduced salinity, cold winters. Each year we are finding the species of planktonic microalgae which are new to the Black Sea.

|

Barnacles - shell-houses of cirripedean crab Balanus improvisus.

|

About 10% of marine organisms inhabiting the modern Black Sea came from the Atlantic during the period of retreating glaciers - it is supposed that there was a water connection between the North Sea and the Black Sea - across the Europe - at the time. Black Sea spiny shark, dogfish Squalus acanthias is thought to be among those North Sea invaders.

Alien Marine Species in Black Sea: Recent Invasions

Young Black Sea ecosystem is still far from equilibrium: new alien invasive species keep coming, old ones becoming extinct as a result of an interaction with invaders. During the last two centuries, many alien species invasions have been facilitated by human activities.

|

Rapana Rapana venosa eating mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis - Black Sea Caucasian Coast

Black Sea - Mollusca - details on

Rapana venosa in the Black Sea

|

Fierce predator - bivalve-eating Pacific gastropod, veined rapa whelk Rapana venosa came here in 1947 from the Chinese coast. Most probably the snail was brought around half of the globe on a ship on its way from Far East to the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, where it was first discovered. Rapana rapidly dispersed around the whole coastline of the Sea, conquered all the Black Sea benthic habitats, proliferated immensely, because there were no predators in the Black Sea to eat this marine snail when it grew over 3-4cm. Starfish that are normal predators of Rapana venosa cannot survive the low salinity of Black Sea. During the past 50 years, Rapana venosa have eaten to extinction half of the bivalvian species that were living in Black Sea before the invasion. Black Sea populations of edible oyster Ostrea edulis and Black Sea scallop Flexopecten ponticus are now on the brink of extinction.

In Black Sea,

Rapana eats decapod crabs too: This Macropipus holsatus crab was killed and digested by Rapana venosa using this hole drilled in the carapace.

Sand bottom near Tuapse.

.

|

After its Black Sea conquest, Rapana venosa entered Mediterranean Sea, and settled (1974) in the brackish parts of the upper Adriatic Sea (Rapana page of Mediterranean Science Commission). We were finding Rapana along the Adriatic coast of Montenegro in 2008.

Rapana venosa invaded Chesapeake Bay at Atlantic US coast in 1990s (local oysters were not threatened by the invader, since they all gone due to overharvesting) and Rio de la Plata Gulf in Uruguay. Recently drilling whelks were found at Brittany coast and in Northern Sea - Dutch coast, and wider Thames estuary. Chesapeake Bay resembles Black Sea by its low salinity; just like in Black Sea there are no natural predators to eat adult Rapana.

In 2007 turkish zoologists reported finding of Asterias rubens seastars (an echinoderm species usual in North-Atlantic) in higher saline near-Bosporus area. In case this invasion (or introduction) becomes successful, and red benthic predators spread along Black Sea coasts, the consequences of that might be quite negative since starfish’s main local food most probably might become bivalves, mussels first of all.

Similarity between Black Sea and Chesapeake Bay conditions probably became an important prerequisite for the earlier successful invasion of ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi from Chesapeake Bay to Black Sea - an alien species invasion that resulted in catastrophic consequences for the whole Black Sea ecosystem.

|

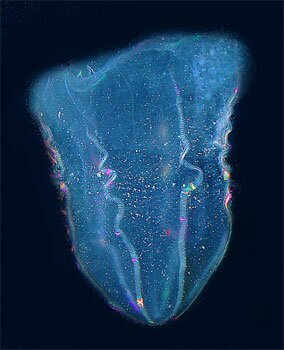

Planktivorous comb jelly - ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi was found from time to time in the Black Sea since the early 1980s. Most probably, it was brought here on ships' ballast waters from the US East Coast. However, it was only in the summer of 1988 when having adapted to the Black Sea, a portion of Mnemiopsis population gave an outburst - and comb jellies virtually filled the upper layer of the Black Sea. The Sea resembled a white jelly in August 1988 - it looked like there were more ctenophores than water. To grow to that extent ctenophores ate most of Black Sea plankton - including fish and invertebrate eggs and larvae. Planktivorous fishes were left without food. The effect relayed through the food web of the Black Sea was that numbers of all studied marine species reduced - including macroalgae and benthic shellfish. The consequences for fisheries expressed in lost catch were estimated as 300-400 millions US dollars a year in the late 1980s; on the other hand fishery itself was one of the causes of the Black Sea fish stock decline.

|

Mnemiopsis leidyi - ctenophore that changed marine life in the Black Sea in 1980s

|

|

Beroe ovata - ctenophore that helped out the Black Sea biota

|

Black Sea marine ecosystem was helped by another ctenophore invasion: carnivorous Beroe ovata came here from Mediterranean in the 1990s. Beroe eats Mnemiopsis - only Mnemiopsis, swallowing it as a whole with a wide mouth-slot. It is a rare case of a very narrow food specialization.

Mnemiopsis population decreased, and during the last years, one could observe the following annual chain of events in the Black Sea ctenophore life: Mnemiopsis of new generation and overwintered ones first appear in cold April water; it is a right time for them, since it is when spring plankton rise. Mnemiopsis population reaches its peak in the middle of summer - water column sometimes is filled by transparent ctenophores. Usually it is at this moment when first Beroe jellycombs can be found; they start grazing on Mnemiopsis. It is very interesting to watch how Beroe gulps Mnemiopsis - just snorkel nearshore in August, and you see it. To the end of September there are no Mnemiopsis in the water, whereas Beroe can be seen everywhere. Having eaten all their food, they fill water column with white threads of their eggs and remains of disintegrated bodies, and completely disappear in late autumn.

|

After the Black Sea invasion, Mnemiopsis has reached the Caspian Sea - apparently having been carried there in ballast waters of ships as earlier; now the living community of this sea-lake undergoes changes similar to those that occurred in the Black Sea.

The ctenophores invasion was an inevitable way of an ecosystem evolution accelerated by the involvement of man. And jellycombs are very beautiful: transparent creatures, hovering in midwater, shimmering with hundreds tiny rainbows running along their bodies - it is their thinnest rowing plates refracting sunlight when moving in matched modes. If you touch them in dark night water, they flash with green light; Mnemiopsis and Beroe are the largest luminescent plankters in the Black Sea.

Anthropogenic Evolution: What We did to the Black Sea Ecosystem

During the past 50 years evolution of the Black Sea ecosystem was mostly determined by human activities, including alien marine species introduction. The Black Sea that once fed the Ancient South-European world, in 20th century became a sink for 175 millions Europeans - with the resulting over-nutrification - or eutrophication, and ensuing phytoplankton blooms and mortality of marine organisms.

The eutrophication problem became most acute in 1970-80s, and it coincided with the peak of overfishing in the Black Sea.

The eutrophication problem became most acute in 1970-80s, and it coincided with the peak of overfishing in the Black Sea.

Officially reported total fish catch in the Black Sea increased from 300000-400000 ton per year in 1970s to 700000-800000 ton in 1980s. Most of it was represented by planktivourous fish, since larger predatory fish species were fished out earlier.

Total nitrogen concentration in the Danube estuary increased from 1.4 mg/l in late 1950s to 7.2 mg/l in 1990; corresponding phosphorus concentrations were 0.10 and 0.33 mg/l. The increase of nutrient load mostly refers to the more intensive use of fertilizers in the regional agriculture in 1970-80s.

Eutrophication was the cause of the phytoplankton blooms, particularly in the Western part of the Black Sea. In some cases it caused marine fauna dye-offs; increased phytoplankton and detritus concentration were reducing the water transparency and consequently the amount of sunlight available for macroalgae. Unique benthic habitat of the shallow North-Western part of the Black Sea, the Zernov's Phyllophora field almost disappeared due to this reason. Brown macroalgae Cystoseira barbata belt of the Black Sea rocky shores has reduced ten-fold.

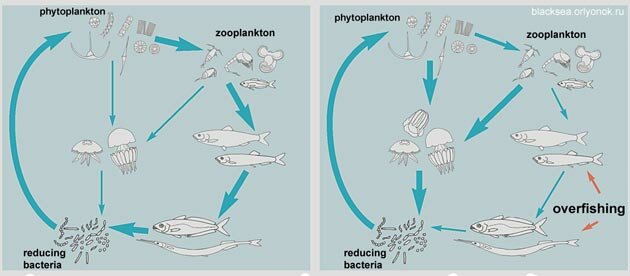

During the period of progressive eutrophication the phytoplankton primary production increased up to three-fold across the whole Sea (up to ten-fold in Western part of the Sea), whereas the planktivourous fish stock was exhausted by overfishing; pelagic community responded by the increase in gelatinous zooplankton biomass. First, the Scyphozoan Aurelia aurita population grew, its biomass exceeding 1000 g/m2 sea surface; later the Ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi intervened.

three-fold across the whole Sea (up to ten-fold in Western part of the Sea), whereas the planktivourous fish stock was exhausted by overfishing; pelagic community responded by the increase in gelatinous zooplankton biomass. First, the Scyphozoan Aurelia aurita population grew, its biomass exceeding 1000 g/m2 sea surface; later the Ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi intervened.

Changes in the Black Sea pelagic foodweb due to overfishing and Mnemiopsis introduction.

The situation was further aggravated by the removal of bonito Sarda sarda from the Black Sea foodweb, due to the overfishing and because of banning its coming to Black Sea for summer foraging through the overpolluted Bosporus Strait; bonito was the major predator of gelatinous plankton in the Black Sea (Dr. Yu.Sorokin hypothesis).

The combined effect of eutrophication and overfishing in the Black Sea was that in 1970s, the main stream of matter and energy within the Black Sea ecosystem was shortcut from the phytoplankton primary producers to bacterioplankton reducers via gelatinous zooplankton.

The Black Sea ecosystem is recovering since early 1990s, when eutrophication slackened and Beroe ovata ctenophore was introduced into Black Sea. The data on the current Danube nutrient loads vary between different sources, however there are no more harmful algal blooms like in 1980s (with the exception of the shallow, brackish, over-nutrified coastal waters of North Western and Western parts of the Sea). Ukrainian biologists report the onset of Zernov's Phyllophora field revival.

Many data show that Black Sea ecosystem absorbed the impact of the Mnemiopsis invasion: scyphozoan jellyfish biomass portion has visibly grown after the Beroe involvement. According to P.P. Shirshov Institute of Oceanology researchers' data, the crustacean zooplankton abundance in the Eastern part of the Sea recovered to the values of the pre-Mnemiopsis years (in corresponding periods of year).

Total fish catches in Black Sea, according to UN FAO data, tons.

UN FAO reports show that catches of the Black Sea anchovy hamsi Engraulis encrasicholus ponticus recovered to the level of late 19970s, the khamsi fishery is almost exclusively Turkish industry now. The Black Sea horse mackerel Trachurus mediterraneus ponticus population is recovering at a slower rate, and still tere is no mackerel in the Black Sea. Most remarkable was the growth of Mugil sojui mullet (Far-Eastern species introduced to the Black Sea in 1980s) population in the Black Sea.

Still the total portion of gelatinous plankton in the Black Sea remains very high, constituting about 90% of total zooplankton biomass in summer.

Black Sea keeps changing in front of our eyes; its rich history of both natural and man-made catastrophes suggests that making predictions on its future is hard.

Excellent books about the Black Sea in English:

Ascherson, N. Black Sea. New York, 1998. - it is both a precise account of the social history of the Black Sea region, and a gripping reading.

Sorokin Yu.I. Black Sea Ecology and Oceanography. (2002) Amsterdam, "Backhuys Publishers". - A most comprehensive reference book on 20th century natural scientific data on the Black Sea.

Zaitsev Yu., Mamaev V. Biological Diversity in the Black Sea: A study of change and decline. New York, UNESCO,1997.